How can you help? AHA president asks

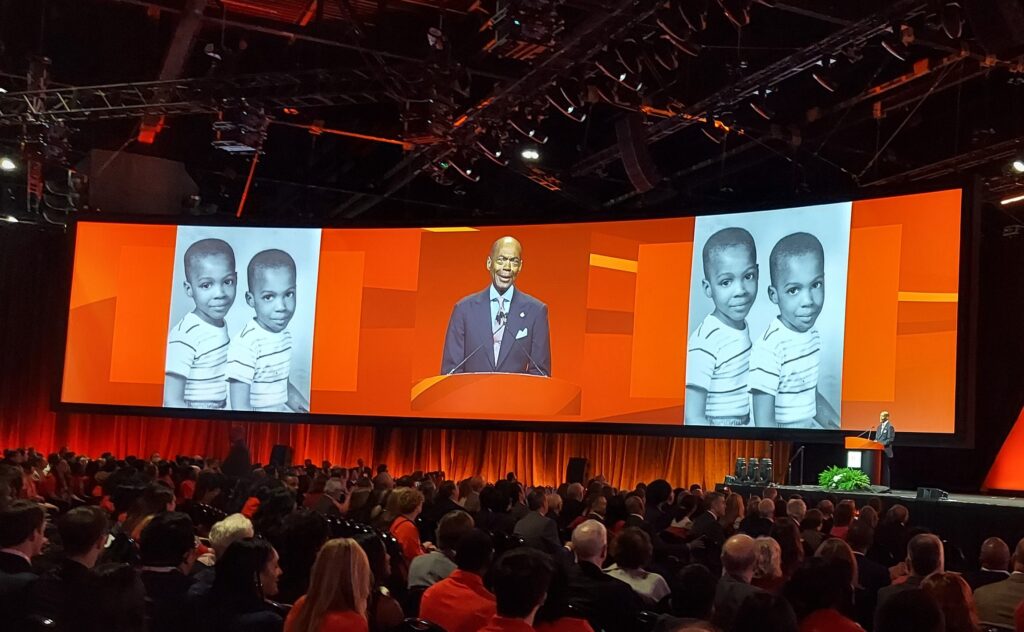

“My arrival in this world was a surprise,” American Heart Association President Keith Churchwell, M.D., FAHA, began his delivery of the Lewis A. Connor Lecture during the Presidential Session on the second day of Scientific Sessions in Chicago. “With no ultrasound available, my parents were only expecting a fourth child – not a fourth and a fifth.”

Introduced by AHA CEO Nancy Brown, Churchwell, past president of Yale New Haven Hospital, paid tribute to his past as he issued a clarion call to the cardiovascular community for the second century of the American Heart Association.

Both of Churchwell’s parents overcame poverty and raised their family in a segregated neighborhood of East Nashville. Churchwell’s father Robert was the first Black journalist at the Nashville Banner. Today, his fedora, trench coat and electric typewriter are on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington. His mother, while raising her children, earned a college degree and taught for 30 years.

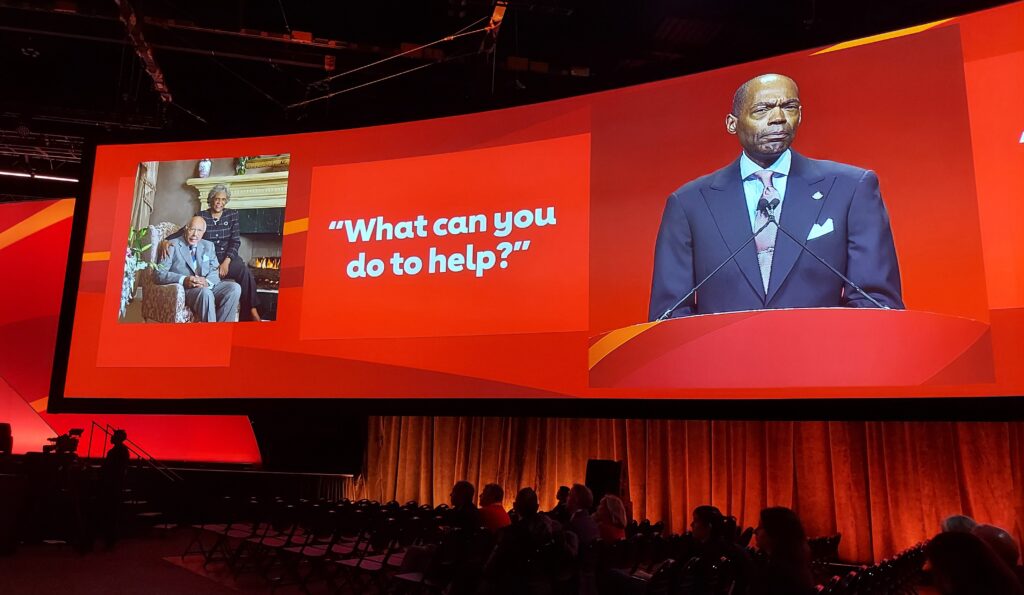

The Churchwells’ constant question for their children was: How can you help?

Three of the Churchwells, Keith, Kevin and Andre, found that answer by becoming doctors, and leaders in their field.

In his address, Churchwell looked at the history of health care in the past six decades, which has changed from being primarily private practice to today’s larger health systems.

“Have they helped?” Churchwell asked. “Yes, IF the patient makes it to the hospital. But growth continues in the number of patients outside the hospital with disease. Efforts to reduce long term risk need to be focused outside the hospital in neighborhoods and communities.”

Dr. Churchwell considered the impact of health systems on health inequities, identifying some of the commonalities of health inequities worldwide.

“Where we live; what we can afford to pay for the care delivered; and the structure of class and social status, created by historical and system obstacles, leading to unequal care,” were the commonalities he identified.

A prime example of those inequities, Churchwell reminded the audience, occurred during COVID, which had hit harder in Black, Hispanic and Pacific Islander communities.

But in his hospital system, outcomes were better than the national average for those groups.

Churchwell attributed that to the hospital system acknowledging that nobody knew how to treat COVID; and finding out on a daily basis what did and didn’t work for each patient.

From that work, Churchwell said the hospital system learned key lessons.

“We must fight and conquer implicit biases that can influence how we treat patients, and we must optimize therapies and hold ourselves accountable to ensure everyone has access to the best care available,” he said. “We must also continually look for ways to enhance our impact, such as leveraging technology and health information to improve results. The final question is, ‘What do we need to do to prepare for what is coming next?’”

Churchwell reminded the audience of this year’s presidential advisory in Circulation that forecast that what would come next could be dire if the upward course of heart disease isn’t mitigated.

Churchwell outlined solutions: aggressively treating risk factors for heart disease; working with partners in government, industry and communities to find ways to improve the social drivers of health; enhancing the working environment for clinicians, scientists, and nurses so they can be more efficient and continue to feel that their work is fulfilling; and making sure that the use of AI improves the ability to deliver quality care, and improves the lives of patients and clinical staff.

He also called on those gathered to ask themselves a version of what his parents had always asked him and his siblings.

“What can we do to help accelerate progress, while at this conference?” he asked. “What can we do to help when we get back to our clinics or labs? And what can we do to help make a difference in our communities.”

Dr. Churchwell extended a clear call to action.

“Over the next century – the American Heart Association’s second century – I urge you to not just imagine what a healthier world could look like, I urge you to help deliver us into that new and better world for everyone, everywhere,” he said.